The New World tropics, or Neotropics, from Mexico in the north to Argentina in the south, contain the richest diversity of flowering plants on earth—more than 100,000 species, or one-third of all plants on earth. From Amazonian jungles to high Andean paramo to the deserts of Mexico, the diversity of these ecosystems is unrivaled. It is home to the greatest mosaic of biodiversity on earth.

Central America occupies an important piece in the puzzle of Neotropic diversification. For more than 50 million years, South America was isolated until the uplift of the Isthmus of Panama formed a connection to North America. A unique tropical flora existed in southern North America before the Isthmus of Panama, but the connection sent a rush of plants from the greater store of diversity in South America north into Central America.

The genus Citharexylum (a group of plants in the verbena family), has spread to colonize most of the Neotropics, including Central American and high Andean ecosystems. Most groups of plants stick to one type of habitat, so Citharexylum presents a rare opportunity to study how diversification might have occurred throughout the Neotropics.

In past fieldtrips, I collected Citharexylum in Argentina, Cuba, Florida, Nicaragua, and Puerto Rico, where all of the species I saw had similar characteristics: large trees with typical broad, tropical-forest leaves, and long inflorescences with many flowers and fruits.

In 2009, I traveled to Peru to collect in the high Andean cloud forests, and was surprised to find stunted trees with small, leathery leaves, and small flowering shoots with only a few flowers. Subsequent collecting in Colombia and Brazil and using tissues from herbarium specimens, have expanded the geographic range of our sampling and enabled us to include desert-adapted species from Mexico.

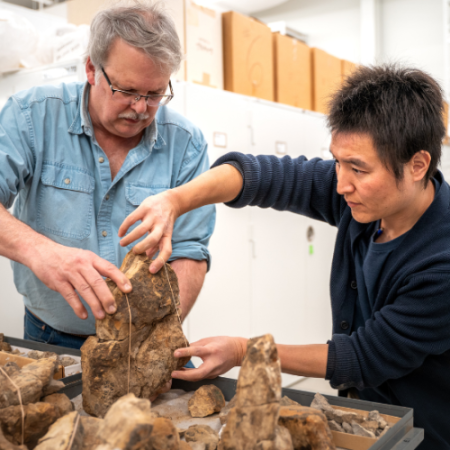

Back in my lab, Ph.D. student, Laura Frost, studied DNA sequences from all of the specimens and noticed a surprisingly ancient split between the South and Central American species, with the Andean species arising from low elevation South American ancestors. Another surprise was that the desert species, occupying perhaps the most stressful environment in which the genus occurs, represent multiple parallel evolutionary adaptations to extreme drought.

These results were based on only a third of the nearly 130 species in this genus, and many more species will need to be included to be able to determine how and when the colonization took place. We also hope to address the important question of whether evolution into different habitats (e.g., Andean cloud forests), or migration to new continents (e.g., Central America) leads to accelerated diversification.

In the coming years, Laura will take this project on as her dissertation research and will travel throughout the Neotropics to collect more pieces of this puzzle.

Through this collecting and research, we’ll move one step closer to understanding how the Neotropics came to have the richest diversity of plants on earth.

For more information, visit the Burke’s “Why Study Evolution” exhibit.