Table of

Contents

Maps:

Culture

Groups of the

All About Baskets:

Basketry

Types and Uses

Materials

Techniques

Designs and

Decoration

Activities:

Weaving a

Plaited Basket

Design

Names

Decorate

Your Own Basket

Glossary

Recommended

Additional Resources

Bibliography

Map of

Tribal

Locations in the Early 1800s

All About Baskets

Basketry

Types and Uses

Basketry

has been practiced for thousands of years by Native peoples of

There are

many different types of baskets, with countless variations on these types made

by different tribes and individual artists.

Some basket types that can be seen in museums are no longer a part of

the daily lives of Native peoples. Many

other kinds of basketry, however, maintain significant roles in Native cultures. The descriptions which follow provide just a

few examples of important types of basketry.

Food Gathering, Storage and

Preparation

Basketry

played an important role in the gathering, storage and preparation of

food. Baskets were (and, in some cases,

still are) used to gather roots, berries, shellfish and other foods. Sturdy burden baskets capable of holding

large and heavy loads were worn on the back and carried using a tumpline. Baskets made for gathering berries were often

woven from flexible materials which allowed the basket to be folded and stored

flat. Containers used to gather

shellfish and other seafood used very open weaves, allowing for easy rinsing

and water drainage.

Once

gathered, food was often kept in storage baskets. These varied in size

depending on the items being stored.

Basketry covers made of cedar bark were used by some tribes to place

over dishes or boxes filled with food.

The

preparation of foods often relied on basketry.

Berries and roots could be dried on woven mats spread out in the

sun. Loosely woven basketry was used to

strain oil from certain kinds of fish.

Baskets

were used for cooking in several ways.

Shellfish could be steamed in openwork baskets. Closely woven, watertight containers were

also used to cook foods. Red-hot rocks

were placed in a water-filled basket, bringing the water to boil and cooking

the contents. As the rocks cooled off,

they were removed from the water with wooden tongs and replaced with newly

heated rocks. As metal cooking vessels

first introduced by European traders became commonplace, the use of basketry

for cooking declined.

Furnishings and Garments

Furnishings

made from basketry include mats, chests, trunks and cradles. Mats are made in a wide range of sizes and

are woven with a variety of materials such as cedar bark, cattail leaves or tule. Mats have been

used for canoe sails, house partitions and for padding on which to sleep and

eat.

Garments

are another important category of basketry.

Rain capes can be made using shredded cedar bark or the flat leaves of

cattail. Both of these materials shed

water, providing excellent protection from the rain. Cedar bark can also be used for making aprons,

skirts and hats. Hats provide protection

from both sun and rain. For the most

efficient barrier to rain, southern Northwest Coat hats are often constructed

from two separate, woven layers. The

inner and the outer hats are joined at the rims. Basketry hats made in a variety of techniques

can be seen today at potlatches, powwows and other special events.

Ceremonial Uses

Ceremonies

may feature basketry which displays crests or signifies prestige. (Crests are family emblems which are

considered owned property.) Woven hats

sometimes have crest designs painted on their exterior. On the northern

A few

baskets are regarded so highly that they are considered crests themselves. Among the Chilkat Tlingit, for example, an enormous basket known as Kuhk-claw, or “Mother Basket,” was woven in

the 1800s. Measuring almost three feet

both in height and diameter, the basket was used to hold large quantities of

food. Through its repeated use and

display at potlatches, the basket earned the status of a crest. Today, this basket is both a source of pride

and a precious heirloom for the family to which it belongs.

Baskets Made for

Baskets

made for sale are an important category of basketry and often comprise a large

percentage of museum basketry collections.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, the volume of baskets produced

for sale to non-Native persons increased dramatically. Basketry became an

important source of income for many families.

This time period coincides with increased collecting efforts by private

individuals and museums. Growing numbers

of tourists came to the western

Basketry Today

While it is

an ancient art, basketry is a tradition which continues to thrive today. In the past, basket making was the domain of

women. Today, both men and women

practice basketry, although it remains a predominantly female art. Contemporary weavers, like their mothers and

grandmothers before them, often achieve positions of great respect in their

communities. Basketry also continues to

provide significant income for skilled weavers.

No longer viewed solely as ethnographic specimens or souvenir art,

Native-made basketry has entered the realm of fine art. Basket makers today sell their wares at powwows,

art galleries and museum shops. In

creating their art, Native weavers continue a living tradition that strengthens

the link between past and present.

Materials

Sources

Materials

used in basketry vary, depending upon the type of basket being made, its

intended function, the tastes of the maker and the materials available. A basket used for heavy loads would use

stiff, sturdy material such as cedar withe or cedar

root. A container made to fold flat

requires flexible material such as spruce root.

A basket made for sale and not intended for actual use can use

especially fine, thin or delicate materials in its construction.

Some of the

more common materials used in basketry include cedar bark, cedar root, spruce

root, cattail leaves and tule. Elements used for decoration include

maidenhair fern stems, horsetail root, red cherry bark and a variety of

grasses. These materials vary widely in

color and appearance. Some have a matte surface, while others, such as red

cherry bark, appear shiny.

Gathering

and Processing the Materials

Most raw

materials used in weaving are harvested or gathered at specific times of the

year. This ensures that the materials

are collected when they are best suited for weaving. Weavers understand the growing cycles of the

natural materials they use and recognize when a tree or plant is ready for

harvesting. Often, special prayers are

said or songs are sung by the weaver while she gathers and processes her

materials.

Most materials are collected in the

spring or early summer. This includes

grasses, which must be picked at just the right time. If it is too early in the season, certain

grasses are too soft or narrow for weaving.

Other kinds, such as reed canary grass, need to be harvested before the

plant blooms. Catherine Pascal, a

We pick it along the highway up the valley before it

blooms. After it blooms, it’s no

good. Then we steam it or put it in

boiling water and leave it on the line for a whole week. Then we cut it up all in bundles and put it

away till we use it (Steltzer 109).

The bark of both red and

yellow cedar is gathered when the tree sap is running, normally between April

and July. The sap allows the bark to be

pulled off easily from the tree. To

obtain a long, even length of bark, the weaver makes a horizontal cut into the

tree several feet from the ground, then pulls the bark

away from the tree. As the strip travels

up the trunk, the weaver backs away from the tree. The strip, usually a few inches wide, is

removed from the tree with a twisting motion.

As long as only one or two strips are taken from the same tree, the

removal of the bark will not harm the tree.

Once

removed, the outer cedar bark is removed from the inner bark by folding and

peeling the bark by hand. Stubborn spots

on the bark may require the use of a knife.

It is the inner bark which is used for basketry. The inner bark is washed, dried and gathered

into bundles. It can now be stored for

later weaving projects.

Spruce or cedar root can be

gathered at any time of the year, although cedar root is often collected in the

spring, at the same time when the bark is harvested. Roots growing along a beach or sandy river

bank are easiest to collect. The most

preferable roots are long, straight and even.

Roots are carefully pulled from the ground by hand or with the help of a

digging implement. This task requires

patience and physical strength. In order not to harm the trees, usually only one root is removed

from each tree.

After they

are gathered, the roots are bundled and heated over a fire. After heating, the roots are unbundled and

pulled through a split wooden stick which removes the outer bark. The roots are then split one or more times, rebundled and stored until needed.

If properly

prepared and stored, materials can be kept for years before use. Although stored dry, materials are soaked in

water before they are used in weaving.

This makes them pliable and easier to use. While the basket maker is working, the

weaving materials and the object being made are constantly moistened to keep

them flexible.

Dyeing

Materials

Grasses as

well as roots, bark and stems are sometimes dyed before they are used in

weaving. There are a number of natural

dye sources which provide a wide palette of colors. Red can be obtained from

wild cranberries, nettle, hemlock bark, alder bark, alder

wood and sea-urchin juice. Lichen, wolf

moss and Oregon grape root provide yellow.

Salal berries are a source for dark blue

color, while copper oxides provide a green-blue pigment. Purple hues can be obtained from

huckleberries and blueberries.

Aniline

dyes, introduced by European traders in the late 1860s, provided brighter

colors and a wider color range than most natural dyes. Many weavers switched to commercial pigments

when they became available, producing baskets with vibrantly colored

designs. Today, some weavers choose to

use commercial pigments for dyeing weaving materials, while many others prefer

to use natural sources for dyes.

The Decline

of Natural Materials

One problem

facing many contemporary weavers is the decline of certain raw materials used

in basketry making. This scarcity is due

in large part to the destruction of natural habitat where raw materials are

found. Clear-cut logging removes old

growth cedars which supply the best tree roots.

Wetland areas, a rich source for many weaving materials, have been

subject to pollutants and draining which kill off or reduce the plant

life. The introduction of invasive,

exotic plant species has also negatively affected many indigenous plants. Additionally, some of the best gathering

places for basketry materials have restrictions on their use. Weavers may be unable to collect or harvest

the materials they need in such places.

Weaving

Techniques

There are three main weaving techniques: coiling, plaiting

and twining. Basketry of the

Coiling

Coiling is

a technique which involves sewing. A

foundation material (such as split root bundles) is coiled upwards and stitched

into place. A pointed tool called an awl

is used to pierce a hole in each coil.

The sewing element (such as the shiny outer surface of a split cedar

root) is then threaded through the hole and sews that coil down to the coil

below it.

Coiled

baskets can be woven so tightly that they hold water. In the past, coiled baskets were also used

for cooking.

On the

Plaiting

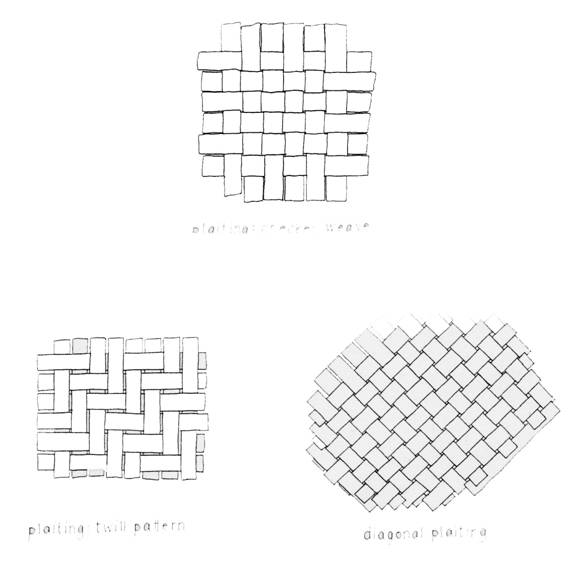

Plaiting,

also known as checker weave, is a straightforward technique in which the weft

crosses over and under one warp at a time.

When a plaited object is flat, such as with a mat, it can be difficult

to distinguish the weft from the warp.

When the

weft passes over or under more than one warp at a time, it results in a

decorative pattern known as twilling.

Plaiting can also be done a diagonal, or bias, weave.

Many twined

baskets start with a plaited bottom. The

weft and warp of the plaited bottom can be split into smaller pieces and become

the warp of the basket sides.

Twining

Twining is

a technique in which two wefts cross over each other between warps. There are numerous variations of twining,

including variances in the number of wefts, the number of warps crossed by the

wefts and the angle of the warps. Each

of these variations changes the surface appearance of the object.

Color

designs on twined basketry can be achieved with false embroidery or overlay.

Both these techniques add a third, colored weft to the usual two wefts. False embroidery is only incorporated into

the outside wefts, making the design visible only on the outer surface of the

object. False embroidery slants in an

opposite direction to the rest of the twining.

The name of this technique is based on the definition of true

embroidery, in which decorative material is added to the surface of an object after it has been completed. False embroidery is added to the surface of

basketry during its making.

Overlay

differs from false embroidery in that overlay’s extra weft is woven into both

the outside and inside wefts of the object.

Depending on the overlay twining technique used, the design may or may

not be visible on the inside surface.

Unlike false embroidery, overlay slants in the same direction as the

rest of the twining.

Designs

and Decorations

Not all

basketry is adorned. Clam baskets and

baskets used for cooking, for example, are usually undecorated. Many other types of basketry, however, have

designs or motifs. Designs can be added

with imbrication, false embroidery or overlay. Designs may also be painted on the exterior

surface of an object after it is completed.

Additionally, variations in the weave can create patterns and raised

textures which form designs.

The designs

often give clues as to who made the basket.

Certain motifs are associated with particular tribes or geographic

areas. The form of the basket may also

reveal clues about its maker. Below are

a few examples of basketry styles which are associated with specific peoples.

Wasco/Wishxam

Wasco and Wishxam

peoples are from the

Wasco/Wishxam basketry is known

for stylized human faces and figures which represent ancestors or the “old

ones.” (“Wishxam”

is pronounced “wish-ram,” with the “r” at the back of the throat, like a French rolled “r.”)

The manner in which the figures are depicted is sometimes called “x-ray

style” due to their skeletal appearance.

The ancient roots of this design style can be seen in a precontact pictograph of a being known as Tsagaglalal (pronounced “tsa-ga-gla-lal”

and meaning “She-Who-Watches”), located near

The most familiar

form of Wasco/Wishxam basketry is a flexible, cylindrical, twined container

known as a Sally bag. Although there are numerous interpretations explaining

the origin of this name, there is not one definitive explanation. In the Wishxam

language, this basket is called akw’alkt.

Twana

Speakers of the Twana language

are the Twana, Skokomish

and Quilcene peoples.

They come from western

Twana weavers are best known

for producing soft twined baskets which feature a horizontal band of animals

woven just below the rim. The animals

may include birds, wolves and dogs.

Although they appear very similar, images of dogs and wolves can be

distinguished from each other by the position of their tails: dog tails point

upwards, while wolf tails point downwards.

Large zigzags may also feature prominently in Twana weaving. This

is not a pattern unique to Twana weavers, however;

many other basket makers, including Klickitat, Nisqually

and

Makah and Nuu-chah-nulth

The home of the Makah people is

the northwestern tip of

Reflective of their whaling heritage, Makah

and Nuu-chah-nulth basketry often includes images of

whales and canoes filled with whalers.

These images originally appeared on whaler’s hats, but later were

incorporated into twined baskets, mats and basketry-covered bottles

made for sale. Whales are sometimes shown being chased or

harpooned by a canoe-full of hunters.

While most of these images show the traditional style of boat used by

whalers, some baskets include images of steamboats or other modern watercraft

aiding in the hunt.

The

whaler’s hat is a distinctive form of basketry found among Makah

and Nuu-chah-nulth peoples. A sign of high rank and prestige, it can be

easily recognized by its conical shape topped by an onion-shaped knob. Drawings made in the 1700s by European

explorers show Makah and Nuu-chah-nulth

chiefs wearing this style of hat.

Haida

The Haida are from the

off the coast of

in

southeastern

Haida weavers have long used simple, solid, horizontal

bands to adorn their twined spruce

root basketry. The basket

shape is usually cylindrical.

Haida artists weave these baskets upside down. The

basket can be supported on a stake

with a wooden form inside.

This style of weaving results in the jog (see glossary) going up

to the right.

Tlingit

The Tlingit are from southeastern

Tlingit basketry is known for geometric designs which

appear

in horizontal bands around the body of the basket.

These designs often have descriptive names such as “leaves

of the fireweed” or “mouthtrack of the woodworm.”

Most Tlingit basketry is twined from finely split spruce

root

and decorated with false embroidery using grasses or fern

stems. During the late 1800s and early 1900s, Tlingit weavers

were

praised in many tourist guidebooks as the most skillful

basket makers on the

Unlike Haida weavers, Tlingit women

weave their

baskets

ride-side up, resulting in a jog which goes down to the right.

Activities

Weave a Plaited Basket

1. Cut all the

way around the outside edges of the “X” shape.

2. Turn the “X”

over and fold (but try not to crease!) one flap along the line that is made

with dots and dashes ( ).

3. Cut along

the three solid lines toward the center rectangle. Stop when you come to the first solid line. Do this for all four flaps. Unfold the flaps. Now you have the “warps” for your basket.

4. Turn the

paper over again and fold and crease along the broken lines ( ). Leave the flaps

so they point up toward the ceiling. Can

you see the beginnings of a basket? Good!

5. Take a long,

thin strip of a paper (called the “weft”) and weave it all the way around the

basket, passing first over and then

under each warp. If you crease the weft

at the corners, it will help you

form the basket shape. Tape or glue the

weft’s ends together where they meet, and cut any

long ends off with your scissors.

6. Repeat Step

5 with your other two paper strips, alternating where you go over and under the

warp (see illustration).

7. Show off

your basket to your friends!

A Twana Basket

Twana people

are from western

Follow these steps to design your own Twana-style

basket:

1. First, draw

a row of wolves around the top of

the basket (keep the wolves within the heavy

black lines).

2. Next, draw

what you think “crow’s shells” look

like. You can put this design anywhere on the basket.

3. Now add the

design “boxes.”

4. Finally,

draw some “flounder beds” on your

basket.

A Haida Hat

The Haida are

from the

Two designs used by Haida weavers

are called “spider’s web” and “snail’s tracks.” Draw what you think these designs look like

on the hat below.

Tlingit

Baskets

The Tlingit

are from southeastern

Tlingit weavers

have names for the different designs they use.

The baskets below have a design name written underneath each

basket. Based on the design name, draw

what you think the design looks like. To

make these Tlingit-style baskets, draw your design in

a band (shown by the dotted lines) around each basket.

“path of the woodworm”

“shaman’s hat”

“fish flesh”

Design Your

Own Basket

Glossary

awl: A pointed tool used in making coiled

baskets. The awl pierces a hole in each

coil to allow the sewing element

to be threaded through and sewn down to the coil below. Traditionally made of bone, today awls are often made from metal.

burden

basket:

A type of basket worn on the back and used for carrying large or heavy loads.

chevron: A geometric design element

shaped like the letter “V.”

coiling: A basketry technique in

which a foundation material (such as split root bundles) is coiled upwards and sewn into place.

crest: A family emblem which is

considered owned property. Crests are

used by central and northern

false

embroidery:

A technique used to decorate twined baskets in which a third, colored weft

element is incorporated into the outer

wefts. These designs are not visible on

the inside of the object. False embroidery slants in an opposite

direction to the rest of the twining.

geometric: (as in “geometric figures”

or “geometric designs”) Design elements which feature geometric shapes such as squares, triangles,

diamonds, chevrons or zigzags.

imbrication: A technique used to decorate

coiled baskets in which the decorative material is folded under each sewing stitch on the outer

surface of the basket. The design is not

visible on the inside of the

basket. Imbrication

folds on a basket resemble rows of corn kernels.

jog: In twined and coiled

baskets, a transition from one row of stitches to the next row. A jog can be up or down to the right or left, depending on how the basket was made (Haida basketry, for example,

usually jogs up to the right; Tlingit baskets jog

down to the right).

overlay: A technique used to decorate

twined baskets in which an additional, colored weft is incorporated into the other wefts. The resulting design may or may not be

visible on the inside of the

object, depending on whether full- or half-twist overlay is used. Overlay design slants in the same direction as the rest of the twining.

pigment:

Colors

obtained from natural or commercial sources. Natural pigments can be

obtained from berries, roots,

bark or minerals. Commercial pigments

often provide more vivid colors than those made

from natural sources.

pitch: The lean of the wefts; the

direction in which a stitch slants (up to the right, for example).

plaiting: A technique in which the

weft strand crosses over and under one warp strand at a time. Also known

as checker or checkerboard weave.

potlatch: An important

precontact: In First Nations history,

the period of time prior to European contact.

Sally bag: Cylindrical, flexible,

twined bags made by Wasco/Wishxam weavers.

start: The beginning weavings of a

basketry object (starts can be seen on the bottom of baskets or the tops of hats).

tule: Also known as bulrush, this

tall, thin plant is used in the construction of mats and bags.

tumpline: A carrying strap attached to

a basket which allows the basket to be carried on a person’s back.

The tumpline is worn across the forehead or chest.

twilling: A variation of plaiting or

twining in which the weft crosses over

more than one warp at a time. This variation in the weave results in diagonal

decorative patterns.

twining: A basketry technique in

which two horizontal strands (wefts) cross over each other between vertical strands (warps). There are a number of twining techniques,

including three-strand, twilled

and wrapped twining.

utilitarian: Made for a specific use,

rather than made solely for aesthetic reasons.

warp: In twined weaving, warps are

the vertical elements. In coiling, warp

refers to the foundation of coils.

weft: The horizontal element which

crosses over warps in twined weaving (also known as “woof”). In coiling,

weft refers to the sewing element.

withe: The thin, strong and

preferably long branches which hang down from the main branches of a tree such as cedar. Withes are used for making burden baskets, basket

handles and rope.

woof: See weft.

Recommended

American

Indian Basketry Magazine. Vols. I-IV (1980-85).

Bierwert, Crisca. Sahoyaleekw: Weaver’s

Art.

Emmons, George T. The Basketry of the Tlingit and the Chilkat Blanket.

Jones, Joan Megan. The Art and Style of Western

Indian Basketry.

Kuneki, Netti, Elsie Thomas and Marie Slockish. The Heritage

of Klickitat Basketry: A History and Art Preserved.

Lobb, Allan. Indian Baskets of the

Marr, Carolyn J. “Salish Baskets from the Wilkes

Expedition.” American Indian Art Magazine 9:3 (Summer 1984): 44-51, 71.

-----. “Wrapped

Twined Baskets of the Southern

-----. “Basketry Regions on

Nordquist, D.L. and

G.E. Nordquist.

Twana Twined Basketry.

Paul, Francis. Spruce Root Basketry of the

Porter, Frank W., III, ed. The Art

of Native American Basketry: A Living Legacy. NY:

Schlick, Mary Dodds.

Stewart, Hillary. Cedar.

Thompson,

Turnbaugh, William A.

and Sarah Peabody Turnbaugh. Basket

Tales of the Grandmothers: American Indian Baskets in Myth and Legend. Peace

-----. Indian Baskets.

Wright, Robin K., Ed.

A Time of Gathering: Native

Heritage in

“Tsimshian

Basketry.” In Tsimshian: Images of

the Past, Views for the Present.

Margaret Seguin, ed.

Additional

Resources

“. . . and Women Wove

It in a Basket.” Bushra Azzouz,

Marlene Farnum and Nettie

Jackson Kuneki.

Documentary video on the life

and work of Klickitat weaver Nettie Jackson.

Baskets of

the Northwest People: Gifts from the Grandmothers. Mimbres Fever.

Two-part video on basketry

from throughout the

Wildwoods Crafts and Basket

Kits.

Basketry kits include

instructions and all materials. “Pine

Needle Basket Kit” and “Coiled Style Basket” are two of the available kits.

Kunstdame.

Paper models of four

Most of these items are available from the

Bibliography:

Emmons, George T. “The Whale House of the Chilkat.” Anthropological Papers of the American

Harless, Susan E., ed. Native Arts of the Columbia Plateau: The

Doris Swayze Bounds Collection.

Holm, Bill. Spirit and Ancestor.

Jones, Megan Joan.

Laforet, Andrea. “Regional and Personal Style in

Marr, Carolyn.

“Continuity and Change in Basketry of

Oberg, Kalervo. The Social Economy of the Tlingit.

Schlick, Mary Dodds.

Steltzer, Ulli. Indian Artists at Work.

Stewart, Hillary. Cedar.

Wright, Robin K., Ed.

A Time of Gathering: Native

Heritage in

Special

thanks to Robin K. Wright, Susan Libonati-Barnes,

Katie Bunn-Marcuse, Dawn Glinsmann

and Deborah Swan for their comments, suggestions and information.

burden basket

storage basket

tourist art basket

activity: match type with suggested

uses

Klickitat style with loops at top - what do you think these

loops were used for?

what kind of material would you

want to use to make the loops?

clam basket:

You and your brother are at the beach gathering clams. You need something to store the clams in, but

you will also have to rinse the sand off the clams once they have been

collected. The clams will also be

heavy. What kind of basket would work

well for your needs? Would you want a

basket with a tight weave or a loose weave?

Would a tight weave allow water to drain from the basket? Do you think you would need a soft basket or

a hard basket to hold all your clams?

Which might offer more strength?

Why? What materials do you think

a hard basket might be made from?

Cooking basket:

watertight

flexible storage container:

You and your friends are out gathering blackberries

What kind of basket would you want? Would you want a large or small

container? Would you want the weave to

be loose or tight? How would you keep

your hands free for berrypicking while still keeping

the basket close to you?

How would you protect the picked berries from the sun? (flexible basket which can be folded over at the top, thus

protecting the berries from the sun and insects)

A small picking basket was used to collect berries; this

smaller basket would be emptied into a larger, sturdy basket worn on the berry

picker’s back.

GALLERY EXPLORATION FOR ENTWINED WITH LIFE

FIND

THE AREA LABELLED “USING BASKETS”

List 2 uses for baskets.

_________________________________________________________________________

FIND

THE AREA WITH THE DISPLAY OF WEAVING MATERIALS

List three materials used in basket making.

_________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________

FIND THE

AREA LABELLED “WEAVER’S ART”

The artists who made these baskets used many different

designs or patterns in their work.

Can you find the following items which have been used in

decorating a basket?

______ a human hand

______ a whale

______ a walrus head

______ a flower

______ a television set

FIND THE

AREA LABELLED “STUDYING BASKETS”

Find the largest basket in this area. What people made this basket?

__________________________________________________________________________________

Find the smallest basket in this area. What people made this basket?

__________________________________________________________________________________

What do you think each of these baskets might have been used

for?

__________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________

What is your favorite basket in this exhibit? Who made this basket? What would you use this basket for?

Draw a picture of the basket.