Shared widely by both football and Native art fans, the blog post on the discovery made its way to the Hudson Museum at the University of Maine, who alerted the Burke to the mask’s location in their collection and offered to loan it to the Burke.

The mask’s journey

The mask made the 3,200 mile journey from Maine to Seattle—thanks to the power of crowdfunding and generous support from Bekins Northwest, the “official mover of the Seattle Seahawks.” Once the mask arrived safely and acclimated to our climate, we began carefully preparing it for public display.

We asked artist Bruce Alfred, a member of the Namgis Band of the Kwakwaka’wakw Nations, who was visiting the Burke, to study the mask. Bruce and our curators uncovered many new details in just a few days.

Scuffs and scratches on the mask show it was used in ceremonies before it was sold. Bruce described how a dancer would enter the big house wearing the mask in its closed position, dancing counterclockwise around the fire—imitating the movements of a large raptor—with firelight reflecting in the mask’s mirrored eyes. At a certain point, the drummers would beat faster and the dancer would dramatically open the mask and reveal the inner human face and long-necked bird rising above.

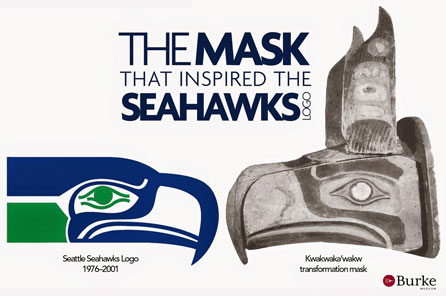

The mask likely represents a supernatural eagle—or thunderbird—transforming into its human form.

The inside of the mask reveals the inner human face and long-necked bird rising above.

Robin K. Wright and Bruce Alfred look closely at a tag on the mask.

A tag in the mask dated 1910 includes a catalog number from the Fred Harvey Company, which operated hotels, restaurants, and Indian marketplaces throughout the southwestern U.S. in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. The Company’s collectors traveled throughout the Southwest, California and along the Colorado River buying art for the marketplaces. They also collected objects from Plains and Alaskan tribes, which offers a possible explanation for how the mask came to be part of the Company collection.

“We knew it was made at the north end of Vancouver Island in the 19th century, but we didn’t know anything else until it came in to the Max Ernst collection,” said Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse, Assistant Director of the Burke Museum’s Bill Holm Center for the Study of Northwest Native Art. Ernst lived in Sedona, Arizona, in the 1940s—suggesting an opportunity for his acquisition of the mask. “We are filling in the gaps in the mask’s history.”

Unveiling and welcoming the mask

We welcomed and blessed the mask at a one-of-a-kind press event on November 18, 2014—which just happens to be the turning point in the Seattle Seahawks season. In fact, they remained undefeated, winning the NFC West championship and divisional playoffs.

Posted: November 18, 2014

A special thanks goes to Kwakwaka’wakw artist Andy Everson, Le-La-La dance leader George Taylor, the Blue Thunder drum line, the Seagals, former Seahawks quarterback Jim Zorn, former Seahawks tight end Ron Howard, and Hudson Museum Director Gretchen Faulkner, for helping us celebrate the mask's arrival at the Burke Museum.

The mask was on display at the Burke Museum as part of our Here & Now: Native Artists Inspired exhibit from November 22, 2014 through July 27, 2015.

Explore More

Keep reading to discover more about the Seahawks mask and its journey to Seattle.